My Articles

AN OVS MARTINI

In the shadow of the mountain: Re-enactors of the 24th form up at Isandlwana.

The Martini-Henry rifle is one of the great classic arms of all time, instantly recognisable as a major tool in the building of the British Empire. Many collectors’ fascination with the Martini began with the defence of Rorke’s Drift depicted in the 1964 film “Zulu“. Although containing minor historical inaccuracies, the film remains a stirring spectacle of courage both by the British and their Zulu opponents. In the film, the late Stanley Baker, in the role of Lieutenant Chard, ascribes their survival as “If it’s a miracle, Colour Sergeant, it’s a short chamber Boxer Henry point 45 calibre miracle”. To which Nigel Green as Colour Sergeant Bourne replies “And a bayonet, Sir! With some guts behind it!”

Historical Background

Peabody’s original design with outside hammer. This is a Peabody supplied to the Spanish.

In technical terms the Martini is often called a “falling block” design, but a more accurate description is a “pivoting block” action – leaving the Alexander Henry, the Guedes and the Sharps as examples of true “falling block” rifles. The pivoting breechblock worked by an underlever was patented by Henry Peabody of Boston in 1862. Peabody’s original design – with an external hammer which had to be cocked by hand – was adopted by Canada, Spain, Romania, Switzerland and several US State Militias.

In Switzerland, Frederick von Martini worked to improve the Peabody action, retaining the pivoting, rear-hinged breech block, but with a self-cocking internal firing pin and coil spring set inside the pivoting block. The very first conflict involving the Martini was a legal battle, when Peabody took von Martini to court for infringing his patent, and lost.

Ironically, when Turkey needed Martinis for the war against Russia in 1878, she was unable to obtain them from the UK, so the Providence Tool Company in the USA manufactured Peabodies for the Turks, but updated to include the much superior self-cocking internal hammer introduced by von Martini.

Contemporary cartridges, from left to right: 10.43x38RF Swiss; modern brass Snider .577; coiled brass 577/450; modern US 45/70; Mauser 11mm (WWI relic); Gras 11mm.

After extensive trials of 120 different actions, and 49 different cartridges, the British Army decided to adopt the Martini action in its new rifle to replace the stop-gap Snider. The best rifling was deemed to be that designed by Alexander Henry of Edinburgh, and combining the action and rifling resulted in the Martini-Henry. Originally the rifle was chambered for a long cartridge, which was awkward to load in the Martini, but it was quickly reworked for the classic Short-Chamber Boxer .577/.450 with its exaggerated bottle-neck shape and more than generous powder capacity (Boxer being the type of centre-fire primer invented by Colonel Boxer, which became popular in the USA, .577inch from the diameter of the lower part of the case, derived from the earlier Snider, and .450 from the upper part of the case, holding the .45inch calibre bullet).

In a desperate fight, victory usually goes to the side whose morale helps it stand firm the longest, and in this the Martini-Henry was a great advantage. Like another great classic single-shot rifle, the Remington Rolling Block, the Martini-Henry inspired great confidence in the young recruits issued with the new breechloaders – despite its reputation for having a ferocious recoil. At a time when metallurgists and chemists were making great strides into the unknown in the science of gunmaking and cartridge design, it gave one a great feeling of security to both see and hear the substantial slab of steel which is the breechblock click up into place, between the base of the large cartridge and the firer’s face.

The exact opposite effect – causing just a split second of doubt – can be generated by looking down the sights of a loaded and cocked straight-pull bolt action rifle. The Ross Model 1910, which could be reassembled after cleaning in such a way that the bolt would not lock into place, is notorious in this respect. And a split-second’s hesitation can be fatal. To say nothing of the lack of confidence generated by the design of the Treuil de Beaulieu issued to the unfortunate French Cent Gardes in 1854: at the moment of pulling the trigger, the firer is looking at the uncovered rear of the loaded cartridge case directly in front of his face!

The impressive power of the huge .577/.450 cartridge resulted in one unique feature, found only on Martinis. On the top right rear of the receiver there is a chequered oval depression, 25mm long by 12mm wide. Placing the tip of the thumb of one’s right hand in this depression, instead of grasping the front of the butt with the thumb held in the more traditional horizontal position, will save the firer from the Martini equivalent of the notorious Chauchat “gifle” or “slap”. In the case of the Martini, if the rifling is fouled from repeated firing, on pulling the trigger the joint of the thumb would impact on the nose with the kick of the 85 grains of black powder behind the 480 grain paper-patched lead bullet. A broken nose can be the result. Placing the thumb in the oval saves the nose and considerable embarrassment.

The smaller and lighter Martini carbine chambered the same cartridge but downloaded to a 410 grain bullet and “only” 70 grains of powder in consideration of the recoil, and to avoid wasting unburned powder in the shorter barrel.

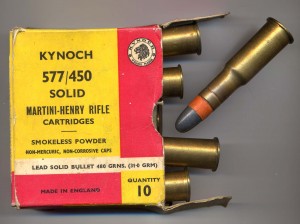

577/450 Cartridges from left to right: An original coiled brass case with a ‘window’; Kynoch drawn brass solid case with smokeless load; NDFS turned brass case; modern Kynamco drawn brass case fired in the OVS Martini with the shoulder blown forward.

Ammunition

Originally cartridges were manufactured in Woolwich Arsenal, where some of the workers were the orphans of British soldiers who had died in service, thus potentially creating more orphans to carry on the trade. The first cases were made of coiled brass foil, which Colonel Boxer intended to uncoil and coil up again on firing, to help seal the breech and aid extraction. Because these orphan boys, on piece-work pay, tended to skimp on the number of layers of brass foil, a small peep-hole or ‘window’ was introduced, so the examiner could check for the presence of the inner layer of foil.

Complaints of coiled brass cartridges jamming in the breech in hot, dusty desert conditions, when the iron cartridge base could be torn off by the extractor, leaving the case body in the chamber, led to the introduction of the one-piece solid-drawn brass cartridge in 1885, although the original coiled brass case continued in use in India into the cordite period.

An original Kynoch box containing 10 cartridges, loaded with smokeless powder, but still with the solid lead paper-patched bullet with no outer jacket. The drawn or turned solid brass cartridge case is still in production by specialist manufacturers around the world today.

Re-enactors of the 60th Regiment on the firing step at Fort Nelson, on a grey day.

In the service of the Queen

“When ‘arf of your bullets fly wide in the ditch,

Don’t call your Martini a cross-eyed old bitch.

She’s human as you are – you treat her as sich,

An’ she’ll fight for the young British soldier.”

(From “the Young British Soldier” by Rudyard Kipling)

Re-enactors of the 60th Regiment volley firing.

During Queen Victoria’s 64-year reign, the British Army was involved in over 60 military campaigns, and fought some 400 battles. The Martini-Henry, adopted in 1871, and first issued to the troops in 1874, bore the brunt of the fighting against Malays, Afghans, Kaffirs, Zulus, Boers, Egyptians and Sudanese, until largely supplanted in front-line service by the Long Lee magazine rifles from 1888 onward.

Re-enactors of the 24th Regiment at Isandlwana.

At Isandlwana, modern research blames the catastrophe which overcame the garrison of the camp not on the ammunition supply but because the Imperial troops were seriously over-extended in the face of overwhelming numbers of their fast-moving Zulu opponents. The defeat was redeemed the same day at Rorke’s Drift and avenged at Ulundi. The belated attempt to save Gordon in Khartoum led to desperate fighting in the Sudan, especially at the battle of Tamai where the square was broken, and bayonets bent. Fighting on the North-West Frontier of India was practically continuous throughout the period, and the last great battle involving the Martini took place at Omdurman in 1898, where Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian Army crushed the forces of the Khalifa and avenged the murder of Gordon. On that day, the 1st Sudanese Regiment under Smith-Dorien were armed with the Martini, and had a close brush with disaster when they were suddenly ambushed by 20,000 brave and ferocious Dervishes in the open desert. Smith-Dorien must have reflected on history repeating itself, as he had been one of the very few survivors of Isandlwana. The Sudanese were fixing bayonets to receive the rush of the Dervishes when an English Regiment, despatched by Kitchener’s staff at the last moment, rushed to their rescue.

The 1st Sudanese were still armed with the Martini, because following the Indian Mutiny of 1857, and right up to the Great War, native troops were usually armed with the previous model of rifle, the more modern rifles being supplied only to the British troops. Thus when the Martini was issued to Imperial troops, the native levies were handed down the Snider. Similarly, when the Magazine Lee-Metford was introduced, native troops received the single-shot .455 Martini-Henry, and later the Martini-Metford in .303 calibre, but still single shot.

Imperial Martinis went through four different Marks: The Mark I first issued in 1874 featured a safety, a polished breechblock top surface, and a chequered buttplate. The Mark II sealed for service in 1877 had a revised trigger, no safety, a blued breechblock top surface and plain buttplate. The Mark III of 1879 had a larger diameter firing pin, a smaller cocking indicator and a different method of fastening the forestock. The long-lever “humped-back” Mark IV first appeared in 1888 as the “Enfield-Martini .402 calibre”, introducing a new smaller-bore round which was never widely adopted. When the Army moved over to the even smaller-diameter .303 round, all Mark IVs were re-barrelled to the old standard 577/450 calibre. The Mark IV was also intended to use a quick-loading device which attached to the left-hand wall of the receiver, but these were never used in action.

British Army Martinis have one puzzling feature. The breechblock pivots on what appears from the left-hand side of the receiver to be a screw. However, inserting a screwdriver blade and turning this “screw” does not result in its removal. It is in fact the open end of a split pin, which has to be drifted out of the receiver, not unscrewed. The later Francotte modification, by moving the cocking indicator lever inside the receiver, allows the entire action to be withdrawn from below, this time by actually removing one screw with the rim of a cartridge case.

Sporters and lookalikes

The Martini was very popular with hunters in Africa and India, as the .577/.450 round could deal with the largest and most dangerous wild game. With the adoption of the .303 round in 1888, many Martini rifles and carbines were re-barrelled to become, firstly Martini-Metfords and then Martini-Enfields. Thousands were sold out of service, and many of these appeared, after a hundred years, from the famous cache in Nepal. Small-calibre Martini action rifles trained generations of shooters, including the author, in either .22 rimfire or .310 Cadet centrefire.

Commercial manufacturers produced thousands of Martinis, and the last variation to appear was the Francotte action made in Liège, Belgium, in which the cocking indicator flips up inside the receiver alongside the breechblock.

Military Martini lookalikes were also manufactured by the Government of Nepal, but internally they are completely different, with an action based not on that of Peabody and von Martini, but on the mechanism of the Westley Richards N° 5 Express rifle.

Genuine and lookalike Martinis were extremely popular in the Middle East, and the so-called “Khyber Specials” were – and still are – a stock item in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The first examples were hand-crafted by local artisans, and were usually betrayed by the misspellings on the receiver side, typically the ‘R’ in the ‘VR’ or the ‘N’ in ‘ENFIELD’ are reversed, and often the date when the artisan made his rifle would lead one to think that Queen Victoria reigned for many years from beyond the grave – as in the photo above. Many unsuspecting US servicemen brought home one of these copies, and to cater to this lucrative market the unscrupulous locals later churned out thousands of factory-made replicas with the spellings corrected and even with fake “rusting” added. Testing by enthusiasts in the USA has revealed that, sooner or later, these crude modern fakes will actually blow up if fired.

Boer rifles

A modern Boer re-enactor firing a Martini.

The last classic military Martinis were made for the Boer Republics of South Africa, just before the turn of the Twentieth Century. Alarmed by the failed Jameson Raid, the Boer Oranje Vrij Staat and the Zuid Africaans Republik desperately shopped around for as many firearms as they could find, to stave off the impending British invasion which became the Second Boer War.

The ZAR purchased new Martinis from Belgium in the later Francotte configuration, as well as buying up Martinis from other sources. They were even grateful to find on the shelf at Steyr the old single-shot Guedes rifles which Portugal had rejected years earlier.

The Free Staters opted for a batch of 3,500 Martinis made in 1897 in Liège for Westley Richards in the classic British Army Mark III configuration.

OVS N° 3295 is from this batch. They were sold on to farmers in the Free State for the sum of four Pounds, from which they are known to collectors as the “Four Pound Rifle”. Compared with the more modern Mauser and Krag magazine repeater rifles used by the ZAR, the Martinis must have appeared a strange choice to an outsider, even when one takes into account the desperation of the small and vulnerable Republics. However, the Martini is strong, simple and very effective. The hardy Voortrekkers would be familiar with it, and of course they knew how much their traditional foes, the Zulus, hated and feared the Martini. Even at the turn of the Century, there would be many native survivors of the battles of the Zulu War who still bore visible evidence of the terrible effects of being struck by the .450 bullet.

OVS rifle N° 3295 in detail

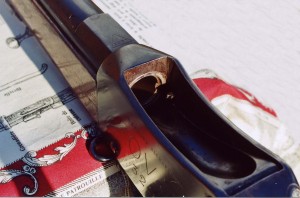

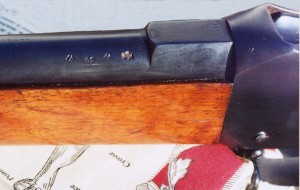

From a distance, it is externally indistinguishable from the British Mark III configuration, with short underlever, small cocking indicator, and the forend fastened by means of a hook into the front of the receiver.

It even has a bayonet bar, although the Boers never ordered any bayonets, planning to fight from long range. In this respect it has a slightly heavier barrel than the British Army model.

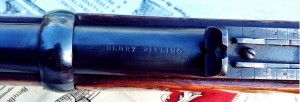

Internally the barrel has nine grooves instead of the seven in British Army Martinis, although it is still of classic Henry design, as shown by the “HENRY RIFLING” stamped into the top surface of the barrel.

Of note are the Liège inspection and proof marks. The date of manufacture, “1897”, is stamped within a large triangle on top of the nocks form.

The rear sight is marked up to “1300”, which must be “yards”, as it is stamped with the broad arrow and therefore appears to have come from a British military rifle. The rear sight may have been fitted as a repair when this Martini was later used in the UK as a target rifle, or it may indicate that second-hand military parts, as evidenced by the bayonet bar, may have been used to fabricate these rifles.

Performance

The OVS Martini shoots very well at 500 yards, and the author had no trouble hitting the centre of the target at Bisley at this range. One notable characteristic is the effect that fitting a bayonet has. Without the bayonet, at 50 metres the rifle shoots consistently 7 inches (200mm) high and 5 inches (127mm) to the right. Fixing a huge yataghan bayonet (as would have been carried by the British Army sergeants) corrects the point of impact to the point of aim. This can apply at up to 100 yards range, so when onrushing Zulus or Dervishes were at some point between 200 and 100 yards away, a commanding officer would have had to quickly make the decision to order “Fix bayonets”, and his troops would have had to be mighty smartish about it. Definitely not the moment to fumble, or even drop your bayonet. With this rifle the author easily won the single-shot class at the HBSA Fixed Bayonet Shoot at Bisley many years ago, in the process even beating the score of several shooters with magazine Mausers. A very efficient weapon system with and without the bayonet.

Parting shots

Apart from the virtually still-born Enfield-Martini quick-loader, only the Norwegians succeeded in turning the single-shot Peabody design into a magazine repeater, with their Krag-Peterson Model 1876. However, the concept of the pivoting block was taken one step further by Danish Lieutenant Schouboue when he designed the famous Madsen light machinegun. The entire barrel and breechblock assembly of the Madsen reciprocates back and forth under the impetus of recoil and muzzle gas, plus the return spring, but inside the moving receiver is a rear-hinged pivoting block. In this case, however, it not only has down and horizontal positions (to load and lock respectively), as in the Peabody / Martini, but it rises to eject the spent case. In this way Schouboue made a repeating pivoting block, and rendered it full auto.

Further reading

The Martini-Henry rifle is a very wide subject. For further information I can do no better than recommend the following sources:

BESTER, Ron, Boer Rifles and Carbines of the Anglo-Boer War

TEMPLE, B.A. and SKENNERTON, Ian, A Treatise on the British Military Martini

SKENNERTON, Ian, Small Arms Identification Series N° 15

Jason ATKINS’ Website at www.martinihenry.com

The Martini-Henry Forum on www.Gunboards.com

Keith DOYON’s www.militaryrifles.com

The works of Rudyard KIPLING.

Acknowledgements

Photographs of OVS N° 3295 are by the author, and the shots of the 24th Regiment, the 60th Regiment and the Boer re-enactors are courtesy of Tim ROSE of the Diehards. The author is grateful for the helpful advice provided by George GEEAR of Chapel Bay Fort, Angle, and Jeremy TENNISWOOD.

© Roger Branfill-Cook, May 2008 and October 2015